ASG Analysis: Unpacking the USMCA: Answers to the Essential Questions

Executive Summary

- On the evening of September 30, the U.S., Canada, and Mexico announced that they had reached agreement on a trade deal, meeting their self-imposed midnight deadline by a few hours.

- The new United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) is set to replace the quarter-century-old North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), pending signing and ratification.

- The USMCA is 12 chapters longer than NAFTA and includes provisions that were not in the original agreement including digital trade, state-owned enterprises, small and medium enterprises, competitiveness, anti-corruption, good regulatory practices, and exchange rate matters.

- The USMCA sets out very high and stringent auto rules of origin that could disrupt regional supply chains.

- The new agreement has stronger intellectual property provisions, which bolster copyright, patent, and trademark protections. However, it has an investor-State dispute settlement mechanism which will exclude Canada and limit its full protection to Mexico’s energy, infrastructure, and telecommunications sectors, while excluding the automobile industry.

- As part of the Trump administration’s strategy to act “tough” on China, USMCA sets forth a requirement for parties to disclose their intention to enter into a free trade agreement with a non-market economy (NME) and allows parties to withdraw from the USMCA should they disagree with the proposed agreement.

- The USMCA is expected to be signed by the leaders of the three countries on November 29, during the G20 summit in Buenos Aires. However, ASG considers it unlikely that Canada and Mexico will sign if the U.S. does not lift its Section 232 steel and aluminum tariffs by then.

- After signature, each country will follow its own ratification procedures. While ASG does not foresee any significant roadblocks to ratification in Mexico or Canada, U.S. ratification is far from assured. A vote on USMCA will likely take place with the new Congress in 2019.

The Basics: unpacking the USMCA

Is the new agreement trilateral, and why is this relevant?

Yes, the USMCA is a trilateral agreement. However, portions of it include bilateral deals. For instance, in agriculture and dispute settlement there are different provisions between Canada and the U.S. and Mexico and the U.S. (more on dispute settlement below).

From an economic perspective, the trilateral deal is relevant because supply chains would have been severely disrupted with three separate bilateral deals. In addition, a trilateral deal makes the region more attractive to foreign investment. From a legal and political perspective, processing a bilateral agreement would have also been controversial under the Trade Promotion Authority (TPA), which was granted authority to modernize a trilateral deal, not a bilateral one.

What are the major differences between NAFTA and USMCA?

The biggest difference is that the USMCA is much broader in scope. Whereas NAFTA only has 22 chapters, the USMCA has 34. It includes areas that were not in the original agreement, such as digital trade, state-owned enterprises, small and medium enterprises, competitiveness, anti-corruption and good regulatory practices, and exchange rate matters. It also includes side letters on distinctive products, on cheese and wine, on auto safety standards, and on U.S. Section 232 actions.

How were the remaining issues resolved?

The U.S. agreed to retain NAFTA’s Chapter 19 dispute settlement provisions regarding unfair trading practices, which provides for binational panel review of antidumping and countervailing duties, but with a reduced scope and coverage. It also accepted Canada’s cultural industries exceptions. In exchange, Canada granted the U.S. greater access to its dairy market, albeit the increased market access is not significantly higher than the one the U.S. would have obtained in the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), and Canada will keep its supply management system.

Why are there export quotas for autos in USMCA whereas there were no quotas in NAFTA?

The export quotas for autos guaranteed in the U.S. Canada 232 Side Letter and the U.S. Mexico 232 Side Letter can be regarded as “insurance” against Section 232 tariffs on autos, which ASG believes are likely to be imposed.

Without the side letters, the USMCA would not be able to protect Canada and Mexico from U.S. tariffs imposed on the basis of national security. According to the side letters, if the U.S. decides to impose 232 tariffs on autos, it will exclude 2.6 million passenger vehicle imports from each country on an annual basis. These vehicles will still need to comply with regional content rules to receive preferential treatment.

Will Mexico be able to meet auto wage requirements?

No. The Center for Automotive Research estimates that on average, Mexican vehicle-assembly workers make less than $8 an hour, whereas workers at auto parts plants make less than $4 an hour. As such, Mexico will not be able to meet the new $16 hourly wage requirements to count towards the regional content requirements in the near future. However, given that 60% of the new 75% regional content requirements are not wage-related, significant auto production could still remain in Mexico.

Could the new regional content rules disrupt supply chains in North America?

Yes. Notwithstanding the feasibility for a significant share of auto production to remain in Mexico, ASG considers that USMCA’s regional content rules could disrupt existing supply chains. If it made economic sense for auto companies to source more products regionally, all production in North America would comply with the existing 62.5% regional content rule. As it is, about 20% of auto production in North America takes place under WTO rules and not under the NAFTA regional content rules.

Given that the new regional content requirements are higher and more complex than existing ones, even more companies could be tempted into using WTO most-favored-nation (MFN) tariffs, which could prompt the U.S. to preemptively slap Section 232 tariffs on autos in order to foreclose access to the North American market for companies not complying with regional content rules. If companies are forced to take actions that go against market forces, car prices in North America could increase, which would adversely affect consumers and automobile exports, given that cars produced in the region would be more expensive. Furthermore, North American auto producers could lose market share in other countries and U.S. auto exports might not contribute significantly to reducing its trade deficit.

What type of protections will foreign investors have under the new agreement? Are they stronger than in NAFTA?

Investor protections under the USMCA are stronger in terms of intellectual property rights than those under NAFTA but are more limited in terms of the investor-State dispute settlement mechanism.

The USMCA will provide stronger copyright, patent, and trademark protection guarantees, especially for pharmaceutical, agriculture, and technology and media sectors. Specifically, the USMCA will protect biologic drugs for 10 years and extend copyright term requirements to life of author plus 70 years (up from 50 years).

The parties have agreed to limit the scope of USMCA’s investor-State dispute settlement mechanism (USMCA Chapter 14, previously NAFTA Chapter 11). Canada will phase out from investor-State dispute settlement provisions, while U.S. and Mexican investors will have full access to the provisions in limited areas including energy, infrastructure, and telecommunications, but not the automobile industry. Canada and Mexico will resolve their investment disputes through the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) provisions, once it enters into force, while Canada and the U.S. will limit themselves to each country’s domestic courts.

Is there an energy chapter in the USMCA?

While there is an energy chapter in NAFTA, the USMCA only has a chapter called “Recognition of the Mexican State’s Direct, Inalienable, and Imprescriptible Ownership of Hydrocarbons.” This chapter states that “The Mexican State has the direct, inalienable, and imprescriptible ownership of all hydrocarbons in the subsoil of the national territory” and that “Mexico reserves its sovereign right to reform its Constitution and its domestic legislation.” While this may appear restrictive, in practice international investors will retain access to Mexico’s hydrocarbons according to the 2013 constitutional reform. Energy will be protected by the new investor-State dispute settlement provisions. ASG assesses that USMCA’s energy-related provisions will provide political cover for López Obrador (given his nationalistic stance on oil), facilitate ratification by the Mexican Senate, and have no material impact on foreign investment in the sector.

What will the USMCA’s pending review in six years mean for investors?

The original Sunset Clause, which called for automatic termination of the agreement after five years unless the three parties agreed otherwise, was significantly watered down.

The USMCA’s minimum “shelf life” is set at 16 years with a review scheduled six years after it enters into force. It can be renewed successively for another 16 years during each review. This provides enough certainty even for investors who expect returns only in the long-term.

Why are there commitments against currency manipulation?

ASG assesses that these provisions are meant to signal U.S. concerns to its other trading partners.

In theory, the parties do not need protection against currency manipulation. U.S. automakers were adamant about the need to include enforceable provisions against currency manipulation during the TPP negotiations to send a signal to Japan and other Asian economies. However, this will not affect Mexico and Canada since both have a floating exchange rate regime and neither has been accused of manipulating their currency to favor exporters.

How will labor and environmental commitments be enforced?

The commitments regarding labor and the environment are much greater in scope and coverage in the USMCA than in its predecessor. Under the USMCA, Mexico must recognize and guarantee collective bargaining rights (see Annex 23-A of Chapter 23).

Furthermore, the parties have agreed on a set of environmental obligations that include prohibitions on harmful fisheries subsidies, protections for marine mammals, new obligations regarding customs inspections of shipments of fauna and flora, and provisions for air quality, marine litter, and forest management.

The dispute settlement mechanisms for labor and environmental disputes under NAFTA are very weak, while the new environmental and labor obligations are now enforceable under the general dispute mechanism.

Was there significant liberalization in government procurement?

No. Under the USCMA, the U.S. and Canada will have access to each other’s procurement markets under the WTO Government Procurement Agreement, and Canada is excluded from the government procurement obligations in Chapter 13, which apply to the U.S. and Mexico. Procurement obligations between Mexico and Canada will follow CPTPP guidelines, after its entry into force.

Will the agreement help reduce corruption in Mexico?

Anti-corruption is covered in USMCA’s Chapter 27. The agreement sets out domestic and international anti-corruption obligations for the countries, which include the application and enforcement of anti-corruption laws.

Anti-corruption matters are not subject to the general dispute settlement mechanism set out in Chapter 31 and as such are less enforceable than the USMCA’s labor and environmental commitments. Nonetheless, one party can request consultations with another party regarding alleged non-compliance with anti-corruption commitments, and "naming and shaming" political pressures can generate strong incentives to comply with Chapter 27 commitments.

What will happen to the Section 232 steel and aluminum tariffs?

In the USMCA, there are no references to existing U.S. steel and aluminum tariffs or Canadian and Mexican countermeasures. The USMCA includes two side letters, the U.S.-Canada 232 Process Letter and the U.S.-Mexico Process Letter, which address only future and not current Section 232 tariffs. These letters stipulate that if the U.S. imposes Section 232 tariffs or import restrictions on Canadian or Mexican goods, it commits to undertake negotiations with both parties for 60 days before the tariffs or quantitative restrictions enter into force.

ASG considers that Mexico and Canada will probably not sign the USMCA unless those steel and aluminum tariffs by the U.S. are removed. The expectation is that the U.S. will remove these tariffs before November 29, which is when the agreement is slated to be signed. The removal of tariffs could still result in quotas for steel and aluminum exports, which would adversely affect downstream users of steel and aluminum, including the automobile, aerospace, and beverage industries, creating inefficiencies and additional costs.

Steps to Ratification

What are the next steps for ratification?

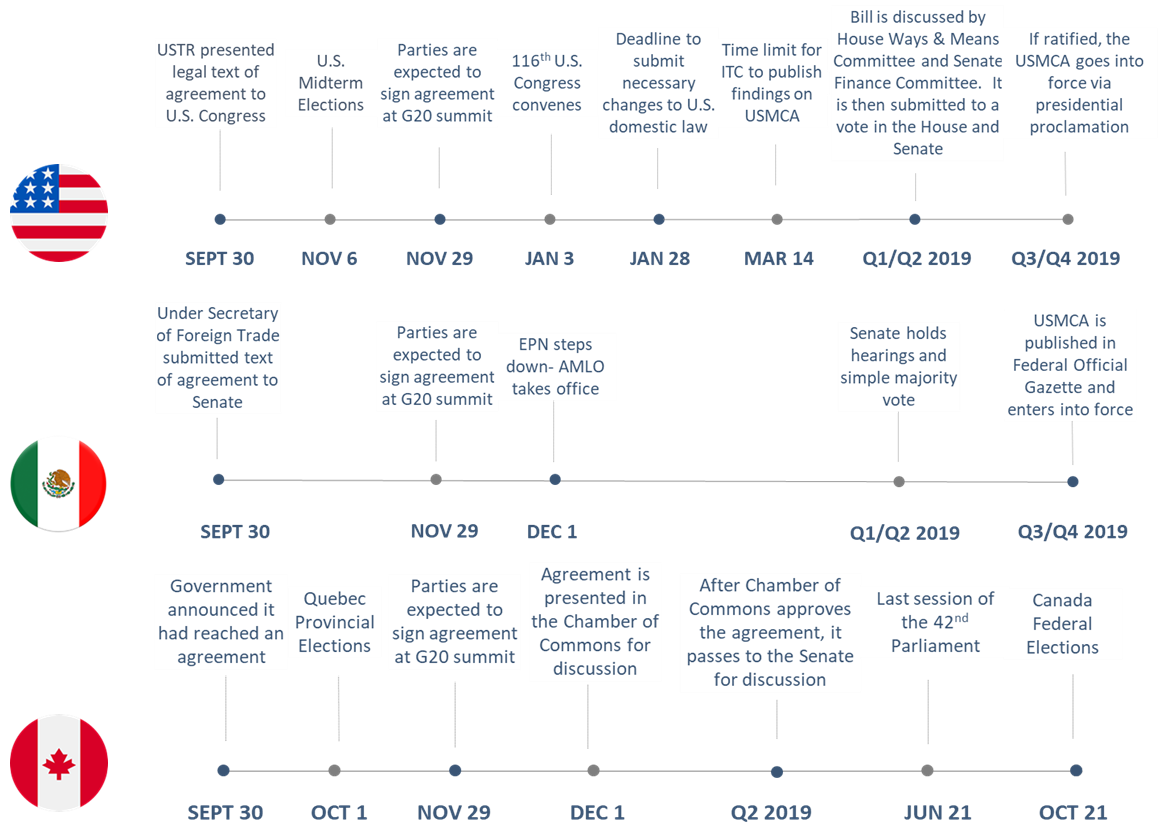

The agreement can be signed 60 days after submission of the legal text to Congress, which took place on September 30. It will likely be signed by the executives of the three countries on November 29, during the G20 summit in Buenos Aires, assuming the U.S. has lifted its Section 232 steel and aluminum tariffs by then.

Signing the agreement does not entail ratification. Each country must follow its own ratification process.

- In Canada, the government must issue an “order in council” to authorize the Prime Minister to sign the agreement. After the deal is signed, the text of the deal must be “tabled” in the House of Commons, allowing 21 days for discussion. The deal must then go through both chambers of Parliament before June 21, 2019, which is the last day the House of Commons is in session under the current government.

- In Mexico, the Senate has to hold hearings and a simple majority vote. The agreement cannot be amended. While President Enrique Peña Nieto will probably sign the agreement before leaving office on December 1, the Senate will probably not vote until next year.

- In the U.S., after the President signs the agreement, the administration has 60 days to notify the necessary changes to U.S. domestic law before the agreement can enter into force (or by January 28, 2019.) Furthermore, the U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) has up to 105 days after the signing of the agreement to submit a report on its economic impact (or by March 14, 2019), although it will probably do so sooner. The administration needs to submit the final text of the implementing legislation 30 days before the bill is introduced in Congress, where it will be discussed by the House Ways and Means Committee and the Senate Finance committee for up to 45 days before it is submitted to a vote, first in the House and then in the Senate. If ratified, the USMCA will enter into force via a presidential proclamation. ASG considers that at the end of the day, the USMCA will be ratified by the U.S.

Approximate Timeline of Ratification in the United States, Mexico, and Canada

It is possible that complementary deals between the U.S. and Canada, and between the U.S. and Mexico, will be added to ensure ratification of USMCA in the United States. During the NAFTA ratification process, then-U.S. Secretary of Commerce Mickey Kantor and then-Mexican Secretary of Commerce Jaime Serra Puche signed a side letter to clarify commitments on sugar, and the North American Development Bank was established in response to the request by some U.S. border states, including California, for funding for environmental issues before they would secure their votes.

Can the agreement be modified before it is ratified?

Yes. The USMCA is “subject to legal review for accuracy, clarity, and consistency” and “subject to language authentication” until a final text is submitted for signature at the end of November. In addition, the House and Senate will not vote on the agreement, but rather on the implementing legislation, which translates the agreement into U.S. domestic law. Mexico and Canada will closely follow the drafting of implementing legislation.

Are there significant ratification challenges in the U.S., Canada, or Mexico?

In Canada, politics may play a role in the agreement’s debate and timing for ratification due to the timing of the October 2019 general elections. However, given that the Trudeau government has a parliamentary majority, ratification is not expected to be challenging.

In Mexico, ASG does not foresee any significant problems to ratification of the USMCA. In Mexico, only the Senate has to ratify international agreements. While members of President-elect López Obrador’s coalition hold a majority in the Senate and some legislators do not like NAFTA or the USMCA, they recognize that the agreement helps macroeconomic stability in Mexico and generates investor confidence.

In the U.S., ratification of the USMCA is far from assured and is expected to be a complicated process. Ratification of trade agreements has become increasingly difficult in Congress, and the USMCA will require ratification by both the House and Senate. ASG does not believe that a vote will take place during the 2018 lame-duck session. The voting will likely take place with the new Congress, where Democrats will likely have control of the House and be loath to give President Trump a legislative victory. Furthermore, labor unions have been lukewarm about the agreement and will want to make sure that the new labor commitments will be enforced. Contentious issues for Republicans include the limited scope of the investor-State dispute settlement mechanism.

Once USMCA is ratified, will it help maintain strong U.S. ties with Canada and Mexico, or will they double down on trade diversification?

Geography is still to a large extent destiny in determining international trade flows. The size of the trading economies and the distance between them affects the amount of trade. As a result, market forces should keep Canadian and Mexican trade and investment concentrated with the United States.

Although the incoming López Obrador administration is not expected to turn away from the U.S., it will likely make concerted efforts to diversify export destinations, import origins, and FDI origins. ASG expects CPTPP and the modernized Mexican agreements with the European Union and the European Free Trade Association to enter into force in 2019, which should boost Japanese and European investments in Mexico.

In July 2018, during a tough phase of NAFTA renegotiation talks, Canada changed the name of the Ministry of International Trade to Ministry of International Trade Diversification. Despite the name change, being a party to the CPTPP, and having a new agreement with the European Union that will help attract more European and Japanese investment, Canada’s largest economic partner will remain (by far) the United States.

USMCA’s Article 32.10 on Non-Market Country FTAs sets forth a requirement for parties to disclose their intention to enter into a free trade agreement with a non-market economy (NME) and allows parties to withdraw from the USMCA should they disagree with the proposed agreement with a NME. This provision could in theory limit the extent of the countries’ relationships with NMEs such as China, which the U.S. considers a non-market economy. However, ASG views this article as part of the Trump administration’s effort to appear “tough” on China, not unlike the aforementioned currency manipulation provisions, and does not expect it to have any material impact on Canada-China and Mexico-China trade relations.

Mexican officials have expressed that this provision in no way curtails the ability of the Mexican government to strike a trade deal with China and that if other parties want to withdraw from the USMCA as a result of a potential trade agreement with China, they can do so. However, the López Obrador administration is unlikely to negotiate an FTA with China; these countries compete in third markets with manufactured exports and there is some concern in Mexico about the geopolitical implications of attracting Chinese investment. Similarly, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has expressed that Canada will continue to pursue deeper trade relations with China.

ASG's Latin America Practice has extensive experience helping clients navigate markets across the region. For questions or to arrange a follow-up conversation please contact Antonio Ortiz-Mena.